μια απόπειρα επιστημονικής προσέγγισης της ανθρώπινης θρησκευτικότητας

an attempt for a scientific approach of human religiosity

"Sedulo curavi humanas actiones non ridere, non lugere, neque detestari, sed intelligere"

—Spinoza, Tractatus Politicus 1:4

⏳ ⌛ First post: October 30, 2008 / Πρώτη ανάρτηση: 30 Οκτωβρίου 2008

.

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

Tuesday, October 30, 2012

Monday, October 29, 2012

Οι πρώτοι Χριστιανοί & ο κόσμος /

Early Christians & the world

Early Christians & the world

“The Christians were strangers and pilgrims in the world around them; their citizenship was in heaven; the kingdom to which they looked was not of this world. The consequent want of interest in public affairs came thus from the outset to be a noticeable feature in Christianity.”

«Οι Χριστιανοί ήταν ξένοι και πάροικοι στον κόσμο που τους περιέβαλλε· το πολίτευμά τους ήταν στον ουρανό· η βασιλεία στην οποία απέβλεπαν δεν ήταν από αυτόν τον κόσμο. Η επακόλουθη έλλειψη ενδιαφέροντος για τις δημόσιες υποθέσεις αποτέλεσε έτσι από την αρχή ένα αξιοσημείωτο χαρακτηριστικό της Χριστιανοσύνης».

—Ernest G. Hardy,

Christianity and the Roman Government: A study in imperial administration,

[Η Χριστιανοσύνη και η Ρωμαϊκή Κυβέρνηση: Μελέτη στην αυτοκρατορική διοίκηση],

G. Allen & Unwin, 1925,

p./σ. 39

[Longmans, Green, and Co. 1894,

p./σ. 51].

[English/Αγγλικά, PDF]

Saturday, October 27, 2012

“Byzantium:

Their ears were uncircumcised” /

“Βυζάντιο:

Τα αυτιά τους ήταν απερίτμητα”

by/του Rafil Kroll-Zaidi

Their ears were uncircumcised” /

“Βυζάντιο:

Τα αυτιά τους ήταν απερίτμητα”

by/του Rafil Kroll-Zaidi

Epiphanius began to interrogate the Blessed One and said: “Tell me, please, how and when the end of this world shall occur? What are the beginnings of the throes? And how will men know that the end is close, at the doors? By what signs will the end be indicated? And whither will pass this city, the New Jerusalem? What will happen to the holy temples standing here, to the venerated icons, the relics of the Saints, and the books?”

—Life of Saint Andrew the Simple, tenth century

Rafil Kroll-Zaidi is the managing editor of Harper’s Magazine. This excerpt is drawn from a feature in the May 2012 issue.

The Turkish emir Osman I, father of the Ottoman dynasty, had a dream. A tree sprang from his loins, and from its roots flowed the great rivers of the world, and its canopy spread from the Caucasus to the Atlas. In the branches nightingales and parrots cried out. Every leaf was a scimitar. A wind blew up that turned these blades toward the cities that lay beneath the tree; most turned toward Constantinople. That city became the emerald in a ring, and the emir slipped the ring on his finger, and awoke.

The Byzantines had said that when, as at its founding in A.D. 330, they were again ruled by an emperor named Constantine, son of a Helena, Constantinople would fall, which in 1453 they were and it did.

The Muslims foretold that a leader who bore the Prophet’s name would take Constantinople, and in 1453 he did and he did.

When the Turks at last breached Constantinople’s walls it was because someone left the door open. At the moment they entered the great church of Hagia Sophia, the priest conducting the mass disappeared into the walls. They found a golden door high in the wall but their masons could not open it.

No witness was found to the death of Constantine XI Dragases Palaeologus, and it is not possible to say with certainty how he died that day or by whose hand or even whether he died at all.

What was Byzantium? The Hellenic east of the Roman Empire had been first provincial holdings and then, with the imperium split between West and East, an equal and conjoined power, and then, with the diminishment of the West, became Rome itself, refulgent.

What were its borders, the appearances of its cities? At greatest extent Byzantium comprised Turkey, Egypt, North Africa, Macedonia, Bulgaria, the Levant, the Sinai, Greece, Illyria, and (when the emperor Justinian I briefly retook the West) Italy and Sicily and Corsica and Andalusia. Pagan classicism—marmoreal, monumental, certain of the primacy of earthly life—yielded to Christian abstraction and introspection. Art was now the ornament and not the celebration of a transitory world; the physical would never again be heroic. And yet what, wondered Bishop Porphyry of Gaza, might Heaven hold if this city of Constantinople could be so grand?

Halfway between Heaven and earth were tollbooths where demons taxed the sins of the Byzantines. Byzantium was efficient in Christ, sophisticated, cautious; a splendor enameled and golden. Its minds were hyaline and humorless. The world was twice as long as it was wide. There was no purgatory.

In 628 the emperor Heraclius summoned Mohammed’s cousin Abu Sufyaan, messenger of the messenger of God, and put to him many questions by which he hoped to weigh the authority of the Prophet. He asked: “Has any among your people ever claimed to be a prophet before him?” He was told: “No.” He asked: “Was any among his ancestors a king?” He was told: “No.” He asked: “Is it the noble among the people or the weak who follow him?” He was told: “The weak.” He asked: “Are his followers increasing or decreasing in number?” He was told: “They are increasing.” He asked: “Does he break his promises?” He was told: “No.” Heraclius concluded: “Verily, if what you say is true, he will rule the ground beneath my feet.”

“Verily you shall conquer Constantinople,” Mohammed promised his followers. “But the Byzantines with horns are people of sea and rock; whenever a horn goes, another replaces it. Alas, they are your associates to the end of time.”

The Byzantines called themselves Greeks (because they were) and also Romans (because they had been). To the Muslims, who had been the Arabs (who had coveted Constantinople even before they were Muslims) but were later the Turks, the Byzantines were usually the Romans (Rum) and sometimes, though these Romans spoke Greek, the Latins (which to the Byzantines meant the barbarians of Western Europe), and sometimes the Children of the Yellow One, who was Esau. The Arabs called the Byzantine emperor (who signed his letters in purple ink EMPEROR AND AUTOCRAT OF THE ROMANS) the Dog of the Byzantines, and by the fifteenth century the sultan of the Ottoman Turks (whom the Muslims farther east called Romans and whom the Byzantines called Trojans) called himself sultan i-Rum in expectation that he soon would be and in recognition that he already, for most purposes, was.

In 912, Harun ibn Yahya was taken prisoner by the Byzantines and brought to Constantinople, where he witnessed the emperor in procession from the palace to the great church, followed by fifty-five thousand two hundred and twelve young Khazars and Turks in stripes and middle-aged eunuchs in white and men and youths and boys and servants and patricians in brocade, and “In his hand is a golden box containing dust. He goes on foot. Every two steps he stops, and his minister says the words ‘Remember death,’ and he stops to open the box, look at the dust, kiss it, and weep.”

What were the laws and practices of the lawgivers? The Great Code of Theodosius forbade the impersonation of nuns by female mimes and the trampling of Jews by gentiles; the edicts of Leo VI permitted eunuchs to adopt; the Orthodox patriarchs anathematized the Manichaeans’ belief that all things fermented are alive.

The rulers of Byzantium were accustomed to blinding their rivals. With ornamental eye scoops, with daggers, with candelabras, kitchen knives, and tent pegs, with burning coals and boiling vinegar, with red-hot bowls held near the face and with bandages that left the eyes unharmed but were forbidden to be removed; sometimes it was sufficient merely to singe the eyelashes, for the victim to bellow and sigh like a lion as a trained executioner pantomimed the act. Sometimes cruelty was intended beyond the enucleation itself, as when the emperor Diogenes Romanus was deposed and “they permitted some unpracticed Jew to proceed in blinding the eyes” and “he lived several days in pain and exuding a bad odor.” In 797 the empress regnant Irene blinded her son Constantine VI and caused an eclipse that lasted seventeen days. Basil II blinded fifteen thousand Bulgarian soldiers, and every hundredth man he left with one eye to lead another ninety-nine, and when these men returned home to their king Samuel he looked upon them and died. Michael V blinded his uncle John the Master of Orphans. The iconoclasts blinded the eyes of the icons.

It was said that the city would fall when ships sailed by over dry land.

Constantinople had a thousand churches and insuperable walls landward and seaward. On the main approach to the palace, only the perfume merchants were permitted their trade. In the imperial throne room was a golden tree in whose branches mechanical birds sang and beside which mechanical lions roared. On a fine cushion next to the levitating Throne of Solomon sat a green goose who screamed if the emperor’s meals were poisoned. The emperor alone could pass back and forth through the membrane separating his court from God’s.

Envoys from the Chinese court reported that “there are jugglers who can let fires burn on their foreheads; make rivers and lakes in their hands; raise their feet and let pearls and precious stones drop from them; and, in opening their mouths produce banners and tufts of feathers in abundance”; that there were jade-colored pearls which coagulated in the saliva of flying birds, lambs who sprouted from the ground and had to be startled into breaking their umbilical cords, and dwarves who worked the fields in fear of being eaten by cranes.

The Byzantines sent to the Fatimid court white peacocks, white ravens, and large bears who played music. They performed divination by thunder, lightning, and the moon.

The emperor Leo the Wise prophesied the doom of Constantinople. (The dreams of man may come from God, accorded the science of the Muslims, but they may come also from the Devil, or from man himself.) Leo created a toad, or a marble tortoise, who roamed the streets at night and consumed all the city’s refuse. He built a bathhouse for the poor that was destroyed by its guardian sagittary statue when the bathkeepers began to charge admission.

The emperor Alexius I built within Constantinople a separate city for wretches. The poor were ephemeral, unsurvived by new generations: different persons grew poor and replaced them.

* Rafil Kroll-Zaidi,

“Byzantium: Their ears were uncircumcised”,

Harper’s Magazine, May 2012 issue.

Friday, October 26, 2012

«Τίς ἐστίν μου πλησίον;»

(Λου 10:29)

Οι «ξένοι», οι φοβίες

& το έθνος

(Λου 10:29)

Οι «ξένοι», οι φοβίες

& το έθνος

Το γνωστό ερώτημα «τις εστίν μου ο πλησίον» (Λουκά 10, 25-37) τίθεται με ιδιαίτερη ενάργεια στην εποχή μας. Πολλές φορές θεωρούμε ότι συνέβη κάποτε στην Ιουδαία, αφορά τους άλλους, τους Σαμαρείτες, και παραμένουμε πρόθυμοι ακροατές του ευαγγελικού λόγου της Κυριακής. Αντίθετα, στην πράξη, όταν ο ξένος είναι κοντά μας, ενεργοποιούνται διάφορα αντανακλαστικά, κάθε άλλο παρά εκκλησιαστικά, και προβάλλονται ανασφάλειες και φοβίες κάθε είδους: φοβίες για την απώλεια της εθνικής και της πολιτισμικής μας ταυτότητας, φοβίες για την απώλεια της καθαρότητας του αίματος, του έθνους, ή του γένους. Η χριστιανική - εκκλησιαστική μας ταυτότητα επικαλύπτεται από την εθνική, τη γλωσσική, την πολιτισμική. Δεν λειτουργούμε ως εκκλησιαστικό αλλά ως εθνικό σώμα.

* Νίκη Παπαγεωργίου,

«Μετανάστες: Κοινωνικές και Θεολογικές διαστάσεις» στο Ξενοφοβία και Φιλαδελφία κατά τον Απόστολο Παύλο»,

Πρακτικά Διεθνούς Επιστημονικού Συνεδρίου, (Βέροια, 26-28 Ιουνίου 2008),

Βέροια 2008, σσ. 241-254.

[Ελληνικά/Greek, DOC]

Η Α. Ζιάκκα & η Ν. Παπαγεωργίου

σχετικά με τις αντιδράσεις Μουσουλμάνων

για την ταινία “Innocence of Muslims”

(«Η Αθωότητα των Μουσουλμάνων»)

σχετικά με τις αντιδράσεις Μουσουλμάνων

για την ταινία “Innocence of Muslims”

(«Η Αθωότητα των Μουσουλμάνων»)

|

|

Αγγελική Ζιάκα και Νίκη Παπαγεωργίου, στο άρθρο: Ρένα Ακριτίδου, «Βλασφημία και Μισαλλοδοξία: Η χαμένη αθωότητα των συμβόλων πίστης»,  HOT DOC τεύχ. 12, Β' Οκτωβρίου 2012, σσ. 62, 63. |

Monday, October 22, 2012

A. M. Jones

on emperor Constantine's conversion /

Ο A. M. Jones

περί της μεταστροφής

του αυτοκράτορα Κωνσταντίνου

on emperor Constantine's conversion /

Ο A. M. Jones

περί της μεταστροφής

του αυτοκράτορα Κωνσταντίνου

+p.+102.jpg) |

Ο προσηλυτισμός του Κωνσταντίνου μπορούμε να πούμε ότι από μια άποψη υπήρξε θρησκευτική εμπειρία αφού, μολονότι το κυριότερο κίνητρό του ήταν η κατάκτηση της κοσμικής εξουσίας, βασιζόταν για να επιτύχει αυτό το σκοπό, όχι στην ανθρώπινη, αλλά στη θεία βοήθεια. Όμως δεν ήταν εμπειρία πνευματική. Ο Κωνσταντίνος δεν ήξερε τίποτα ούτε ενδιαφερόταν καθόλου για τη μεταφυσική και ηθική διδασκαλία του Χριστιανισμού όταν έγινε πιστός του Θεού των Χριστιανών. Απλώς ήθελε να έχει συμπαραστάτη έναν ισχυρό Θεό, που, όπως πίστευε, αυθόρμητα τού είχε προσφέρει ένα σημείο. Ο προσηλυτισμός του αρχικά οφείλεται σ' ένα μετεωρολογικό φαινόμενο που έτυχε να δει σε μια κρίσιμη στιγμή της σταδιοδρομίας του.

* Arnold M. Jones,

Constantine and the conversion of Europe,

The English Universities Press, 1965,

p./σ. 102.

Ελληνική μετάφραση:

Αλέξανδρος Κοτζιάς,

Ο Κωνσταντίνος και ο εκχριστιανισμός της Ευρώπης,

εκδ. Κέδρος, 21983,

σσ. 97, 98.

Sunday, October 21, 2012

Saturday, October 20, 2012

θεός at John 1:1:

“God”, “a God”,

or “a divine being”?

“God”, “a God”,

or “a divine being”?

The Gospel, by John:

translated from the Greek

on the basis of the common English version,

American Bible Union, 1859,

p./σ. 1.

translated from the Greek

on the basis of the common English version,

American Bible Union, 1859,

p./σ. 1.

Prof. A. F. Rainey's efforts

for supporting the form "Yahweh"

of the Tetragrammaton

admitted that were fruitless

even after a decade /

Οι προσπάθειες του καθ. A. F. Rainey's

για να υποστηρίξει τη μορφή "Γιαχβέ"

του Τετραγράμματου

έγινε παραδεκτό ότι ήταν άκαρπες

ακόμη και ύστερα από μία δεκαετία

for supporting the form "Yahweh"

of the Tetragrammaton

admitted that were fruitless

even after a decade /

Οι προσπάθειες του καθ. A. F. Rainey's

για να υποστηρίξει τη μορφή "Γιαχβέ"

του Τετραγράμματου

έγινε παραδεκτό ότι ήταν άκαρπες

ακόμη και ύστερα από μία δεκαετία

An editorial note in BAR, November/December 1984 (“Who or What Was Yahweh’s Asherah?” BAR 10:06) states that the pronunciation Yahweh for the Tetragrammaton is “by scholarly convention.” It should be noted that there are many strong linguistic and epigraphic arguments in favor of Yahweh as the correct form. [...] So Yahweh is not just some sort of “scholarly convention.”

—Prof. Anson F. Rainey,

“How Was the Tetragrammaton Pronounced?”,

Biblical Archaeology Review,

“Queries & Comments” Jul/Aug 1985.

Ya done it again! In a footnote to J. Glen Taylor’s article (“Was Yahweh Worshiped as the Sun?” BAR 20:03), you say: “No one knows how YHWH was pronounced, but it is usually vocalized as Yahweh.” This, despite the fact that you had published my letter, “How was the Tetragrammaton Pronounced?” (Queries & Comments, BAR 11:04), in which I gave the epigraphic and linguistic evidence in support of the pronunciation “Yahweh” (I’m still getting correspondence from all over the world in response to that letter). [...] This is not hocus-pocus. Any layman can readily comprehend the equation. [...] Obviously, my letter in 1985 did not impress you. But the evidence for Yahweh as the correct pronunciation for the Sacred Name is at least as strong as the view that Sennacherib destroyed Lachish Stratum III.

—Prof. Anson F. Rainey,

“How Yahweh Was Pronounced”,

Biblical Archaeology Review,

“Queries & Comments.” Sep/Oct 1994.

Friday, October 19, 2012

1 Corinthians 7:17 / 1 Κορινθίους 7:17,

The New Covenant, Commonly Called the New Testament:

Peshiṭta Aramaic Text with a Hebrew Translation:

יהוה and θεός

in the Hebrew text /

יהוה and θεός

στο εβραϊκό κείμενο

The New Covenant, Commonly Called the New Testament:

Peshiṭta Aramaic Text with a Hebrew Translation:

יהוה and θεός

in the Hebrew text /

יהוה and θεός

στο εβραϊκό κείμενο

Εἰ μὴ ἑκάστῳ ὡς ἐμέρισεν ὁ κύριος,

ἕκαστον ὡς κέκληκεν ὁ θεός, οὕτως περιπατείτω.

καὶ οὕτως ἐν ταῖς ἐκκλησίαις πάσαις διατάσσομαι.

(NA28)

Only, let every one lead the life

which the Lord has assigned to him,

and in which God has called him.

This is my rule in all the churches.

(RSV)

Μόνο, όπως ο Ιεχωβά έχει δώσει μερίδα στον καθένα,

ας περπατάει ο καθένας έτσι όπως τον έχει καλέσει ο Θεός.

Και έτσι παραγγέλλω σε όλες τις εκκλησίες.

(ΜΝΚ βάσει WH)

Πάντως, ο καθένας ας κανονίζει την πορεία του

σύμφωνα με το χάρισμα που του έδωσε ο Θεός

και σύμφωνα με την κατάσταση στην οποία ήταν

όταν τον κάλεσε ο Κύριος.

Αυτή την εντολή δίνω σε όλες τις εκκλησίες.

(ΜΠΚ βάσει του ΒυζΚ)

—1 Corinthians / Κορινθίους 7:17

ספר הברית החדשה: נסח הפשיטתא בארמית עם תרגום עברי

The New Covenant, Commonly Called the New Testament:

Peshiṭta Aramaic Text with a Hebrew Translation,

Jerusalem: The Bible Society in Israel-

The Aramaic Scriptures Research Society in Israel, 1986 /

2nd edition.

Ed. Bishop Jacob Barday and Professor Massimo Pazzini.

Jerusalem: The Bible Society in Israel-

The Aramaic Scriptures Research Society in Israel, 2005.

J28

וְאוּלָם אִישׁ אִישׁ כְּפִי שֶׁחָלַק לוֹ יְהוָֹה,

וְאִישׁ אִישׁ כְּפִי שֶׁקְּרָאוֹ הָאֱלֹהִים, כָּךְ יִתְהַלֵּךְ

וְכָךְ גַּם לְכָל הַקְּהִלּוֹת אֲנִי מְצַוֶּה.

“But each man according to what YHWH apportioned to him,

and each man according to what God called him, thus he should behave,

and thus also I command for all the congregations.”

—Hebrew text / Εβραϊκό κείμενο

אֵלָּא אנָשׁ אנָשׁ אַיך דַּפלַג לֵהּ מָריָא.

ואנָשׁ אַיך דַּקרָיהי אַלָהָא הָכַנָּא נהַלֶּך

ואָף לכֻלהֵין עֵדָתָא הָכַנָּא מפַקֵּד אנָא

“But each man according to what the Lord apportioned to him,

and each man according to what God called him, thus he should behave,

and thus also I command for all the congregations.”

—Peshiṭta - Syriac/Aramaic text /

Πεσίτα - Συριακό/Αραμαϊκό κείμενο

Thursday, October 18, 2012

Wednesday, October 17, 2012

Γένεση 1:6-8:

Το «στερέωμα»

με την έννοια του εκπετάσματος /

Genesis 1:6-8:

The term "στερέωμα" (firmament)

meaning "expanse"

Το «στερέωμα»

με την έννοια του εκπετάσματος /

Genesis 1:6-8:

The term "στερέωμα" (firmament)

meaning "expanse"

|

| * |

|

Митрополит Платон, Православное учение, или сокращенное христианское Богословие, с прибавлением молитв и рассуждения о Мелхиседеке. СПб, 1765, p./σ. 14. |

|

Πλάτωνος Μητροπολίτου Μόσχας, Ορθόδοξος διδασκαλία είτουν Σύνοψις της Χριστιανικής θεολογίας, μετάφρ. Α. Κοραή, Κέρκυρα: Τυπογραφία της Κυβερνήσεως, 1827 (11782), σ. 13. |

+p.+14.png) |

Platon II Metropolitan of Moscow, Κατήχησις The great catechism of the holy catholic, apostolic, and Orthodox Church, abridged ed., London 1867, p./σ. 14. |

|

* |

The concordat

between the Byzantine emperor

& the Eastern Orthodox Church

at 14th century /

Το κονκορδάτο

μεταξύ του Βυζαντινού αυτοκράτορα

& της Ανατολικής Ορθόδοξης εκκλησίας

κατά τον 14ο αιώνα

between the Byzantine emperor

& the Eastern Orthodox Church

at 14th century /

Το κονκορδάτο

μεταξύ του Βυζαντινού αυτοκράτορα

& της Ανατολικής Ορθόδοξης εκκλησίας

κατά τον 14ο αιώνα

A new situation arose after the capture of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade in 1204. The emperor in Asia Minor had an important advantage over his rival in Western Greece because he had the patriarch with him. Working in concert, emperor and patriarch established Nicaea as the political and ecclesiastical capital of a reconstituted East Roman empire. In 1261 Michael VIII Palaeologus retook Constantinople. His entry into the city was more of a religious than a military occasion as he made his way on foot to Hagia Sophia preceded by the icon of the Hodegetria. Eleven years later, he issued a jubilant chrysobull to mark the occasion of the ‘apokatastasis of the Romans’, restoring valuable properties to Hagia Sophia and bestowing gifts and honours on the patriarch Joseph ‘since God, because of his great favour towards me has entrusted to my reign the epistemonarkhian’. The chrysobull was drawn up in 1272 ‘in which year our pious and ‘‘God-impelled’’ [theoprobletos] power has signed it’. Deno Geanakoplos comments: ‘Note the use here of theoprobletos, a term which was then and today still is applied to a bishop, and which was probably used here by Michael purposely in order to point up once again his selection as the chosen instrument of God’s will’. Michael did well to emphasise his role as epistemonarkhes of the Church and instrument of God’s will. The patriarch Joseph, who had legitimised his succession by absolving him from the sin of blinding the young John IV Lascaris, was turning away from him because of his policy of pursuing union with the Elder Rome. After the union of 1274, Joseph was replaced as patriarch by the more compliant John Beccus, but Michael could not force acceptance of the union. After Michael came a period of rapid political decline. The Church, however, flourished. As Ostrogorsky observes, ‘While the state was disintegrating the Patriarchate of Constantinople remained the centre of the Orthodox world, with subordinate metropolitan sees and archbishops in the territories of Asia Minor and the Balkans now lost to Byzantium, as well as the Caucasus, Russia and Lithuania.’

The shifting balance between patriarch and emperor reached a critical point in the latter part of the reign of Michael VIII’s great-grandson, John V. John, as already mentioned, became a Roman Catholic in 1370. His chief minister for much of his reign, Demetrius Cydones, was also a Roman Catholic. In practice the Orthodox Church was left to regulate its own affairs without imperial interference under a succession of able pro-hesychast patriarchs from Kallistos I to Antony IV all through the second half of the fourteenth century. So what was the emperor’s role? In this unprecedented situation John V needed guidelines. Accordingly, at some time in the 1380s he convoked the standing synod at the Stoudios monastery and asked the then patriarch, Neilos, to specify the emperor’s role in the government of the Church. The resulting document has been described, not entirely misleadingly, as a concordat. It sets out in nine articles the emperor’s rights with regard to the Church. These are:(1) The emperor can veto the election of a metropolitan.

(2) He can move bishops and amalgamate bishoprics.

(3) He sanctions nominations to the high offices in the patriarchal administration.

(4) He must respect the boundaries of dioceses.

(5) He is immune from all patriarchal censure.

(6) He can keep in Constantinople or return to their dioceses bishops who come to the capital on important business.

(7) He can exact from every new bishop an oath of loyalty to his person and the empire.

(8) He can make all bishops sign synodal acts.

(9) The bishops in their turn are not to propose for a diocese a candidate who is not a friend of the emperor.

These all concern administrative matters. There is no mention of the sacral aspects of the imperial office. The emphasis is entirely on the emperor’s indispensable role as epistemonarkhes. It is significant that two vital imperial prerogatives did not even come up for discussion: the right to convoke an ecumenical council and the right to appoint the ecumenical patriarch. These were simply taken for granted.

* Norman Russell,

"One faith, one Church, one emperor: the Byzantine approach to ecumenicity and its legacy",

International journal for the Study of the Christian Church,

Volume 12, Issue 2, 2012

Special Issue: Questions for Orthodox Ecclesiology: Thessaloniki Papers,

p./σ. 125 [122-130].

Monday, October 15, 2012

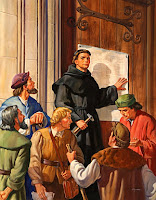

Disputatio pro Declaratione

Virtutis Indulgentiarum

The 95 theses of Martin Luther /

Οι 95 θέσεις του Μαρτίνου Λούθηρου

Virtutis Indulgentiarum

The 95 theses of Martin Luther /

Οι 95 θέσεις του Μαρτίνου Λούθηρου

1. Όταν ο Κύριος μας Ιησούς Χριστός είπε, «μετανοείτε» (Ματθ. δ17), ήθελε ολόκληρη η ζωή των πιστών να είναι μια ζωή μετάνοιας.

2. Η φράση αυτή δεν μπορεί να κατανοηθεί σαν να αναφέρεται στο μυστήριο της μετάνοιας, δηλαδή, στην εξομολόγηση και την ικανοποίηση, όπως παρέχονται από τον κλήρο.

3. Ωστόσο δεν σημαίνει απλώς και μόνο εσωτερική μετάνοια. Η τελευταία δεν έχει αξία παρά μόνο αν παράγει διάφορες μορφές εξωτερικής ταπείνωσης της σάρκας.

4. Η τιμωρία της αμαρτίας διατηρείται όσο παραμένει το μίσος προς το εγώ (δηλαδή, η πραγματική εσωτερική μετάνοια), άρα μέχρι την είσοδο μας στη Βασιλεία των Ουρανών.

5. Ο Πάπας δεν επιθυμεί ούτε είναι ικανός να συγχωρήσει οποιεσδήποτε τιμωρίες, εκτός από εκείνες που έχει επιβάλλει η δική του εξουσία ή εκείνη των εκκλησιαστικών κανόνων.

6. Ο Πάπας δεν μπορεί να συγχωρήσει οποιαδήποτε ενοχή, παρά μόνο δηλώνοντας και δείχνοντας ότι αυτή η ενοχή έχει συγχωρηθεί από τον Θεό. Ή, ακριβέστερα, συγχωρώντας την ενοχή σε περιπτώσεις που επαφίενται στην κρίση του. Αν κάποιος περιφρονήσει το δικαίωμα του να δώσει άφεση στις περιπτώσεις αυτές, ασφαλώς η ενοχή θα παραμείνει ασυγχώρητη.

7. Ο Θεός δεν δίνει άφεση σε κανέναν εκτός και αν την ίδια στιγμή ο άνθρωπος ταπεινωθεί σε όλα τα ζητήματα και δηλώσει υποταγή στον ιερέα, τον εκπρόσωπο Του.

8. Οι εκκλησιαστικοί κανόνες της μετάνοιας επιβάλλονται μόνο στους ζωντανούς και, σύμφωνα με τους ίδιους τους κανόνες, τίποτε δεν μπορεί να επιβληθεί στους αποθνήσκοντες.

9. Επομένως, το Άγιο Πνεύμα, που δρα μέσω του Πάπα, είναι καλό προς εμάς στο βαθμό που ο Πάπας στις αποφάσεις του πάντοτε εξαιρεί το άρθρο περί θανάτου και ύψιστης αναγκαιότητας.

10. Οι ιερείς δρουν με άγνοια και κακία, στην περίπτωση των αποθνησκόντων, όταν επιφυλάσσουν γι' αυτούς εκκλησιαστικές τιμωρίες για το καθαρτήριο.

11. Τα ζιζάνια της μετατροπής της εκκλησιαστικής ποινής σε ποινή του καθαρτηρίου προφανώς σπάρθηκαν ενόσω οι επίσκοποι κοιμόνταν.

12. Σε παλαιότερες εποχές οι εκκλησιαστικές ποινές επιβάλλονταν όχι μετά, αλλά πριν την άφεση, ως δοκιμές πραγματικής μεταμέλειας.

13. Οι αποθνήσκοντες απελευθερώνονται με τον θάνατο τους από όλες τις ποινές, είναι ήδη νεκροί σε ό, τι αφορά το κανονικό δίκαιο και έχουν δικαίωμα να ελευθερωθούν από αυτό.

14. Η ατελής ευσέβεια ή αγάπη (προς τον Θεό) εκ μέρους του αποθνήσκοντος συνοδεύεται κατ' ανάγκη από μεγάλο φόβο, και όσο μικρότερη είναι η αγάπη, τόσο μεγαλύτερος είναι ο φόβος.

15. Αυτός ο φόβος και ο τρόμος επαρκούν, για να μην αναφερθούμε σε άλλα, για να αποτελέσουν την ποινή του καθαρτηρίου, καθώς είναι πολύ κοντά στη φρίκη της απόγνωσης.

16. Η κόλαση, το καθαρτήριο, και ο ουρανός μοιάζουν να διαφέρουν μεταξύ τους όσο η απόγνωση, ο φόβος, και η βεβαιότητα της σωτηρίας.

17. Προφανώς οι ψυχές στο καθαρτήριο έχουν εξίσου ανάγκη την αύξηση της αγάπης όσο την ελάττωση της φρίκης.

18. Προφανώς δεν έχει αποδειχθεί, είτε από τη λογική είτε από τις Γραφές, ότι οι ψυχές στο καθαρτήριο βρίσκονται έξω από την κατάσταση την αξιομισθίας, ή ότι δεν είναι σε θέση να αυξηθούν ως προς την αγάπη.

19. Ούτε φαίνεται να έχει αποδειχθεί ότι οι ψυχές στο καθαρτήριο, τουλάχιστον όχι όλες, είναι βέβαιες και σίγουρες για τη σωτηρία τους, έστω και αν εμείς οι ίδιοι είμαστε απολύτως βέβαιοι γι' αυτό.

20. Επομένως ο Πάπας, όταν χρησιμοποιεί τις λέξεις «απεριόριστη άφεση όλων των ποινών» στην πραγματικότητα δεν εννοεί το σύνολο των ποινών αλλά μόνο εκείνες που έχει επιβάλλει ο ίδιος.

21. Άρα, αυτοί,οι ιεροκήρυκες των συγχωροχαρτιών σφάλλουν όταν λένε πως ένας άνθρωπος έχει συγχωρηθεί για κάθε ποινή και έχει σωθεί μέσω των παπικών συγχωροχαρτίων.

22. Μάλιστα, ο Πάπας δεν δίνει άφεση σε καμία ποινή στις ψυχές στο καθαρτήριο, σύμφωνα με το κανονικό δίκαιο, την οποία οι ψυχές έπρεπε να έχουν πληρώσει όσο ζούσαν.

23. Αν η άφεση κάθε είδους ποινής μπορούσε να χορηγηθεί σε οποιονδήποτε, ασφαλώς θα χορηγούνταν μόνο στους τελειότερους, δηλαδή σε ελάχιστους.

24. Για τον λόγο αυτό, οι περισσότεροι άνθρωποι έχουν εξαπατηθεί από αυτή τη γενικευμένη και εύκολα παρεχόμενη υπόσχεση για απελευθέρωση από την ποινή.

25. Η εξουσία που ο Πάπας έχει εν γένει πάνω στο καθαρτήριο αντιστοιχεί στην εξουσία που έχει οποιοσδήποτε επίσκοπος ή εφημέριος στη δική του επισκοπή ή ενορία...

26. 0 Πάπας κάνει πολύ καλά όταν χορηγεί άφεση σε ψυχές στο καθαρτήριο, όχι με τη δύναμη των κλειδιών, την οποία δεν έχει, αλλά μεσολαβώντας γι' αυτές.

27. Κηρύσσουν μόνο ανθρώπινες διδασκαλίες όσοι λένε πως μόλις τα νομίσματα κουδουνίσουν στο χρηματοκιβώτιο, η ψυχή φεύγει από το καθαρτήριο.

28. Είναι βέβαιο πως μόλις τα νομίσματα κουδουνίσουν στο χρηματοκιβώτιο, ίσως αυξηθεί το κέρδος και η πλεονεξία, αλλά όταν παρεμβαίνει η εκκλησία, το αποτέλεσμα βρίσκεται αποκλειστικά και μόνο στα χέρια του Θεού.

29. Κανείς δεν γνωρίζει αν όλες οι ψυχές στο καθαρτήριο επιθυμούν να λυτρωθούν, καθώς έχουμε τις εξαιρέσεις του Αγ. Σεβερίνου και του Αγ. Πασχάλιου, σύμφωνα με ένα μύθο.

30. Κανείς δεν είναι σίγουρος για τη δική του μεταμέλεια, και ακόμη λιγότερο για το ότι έχει λάβει ολοκληρωτική άφεση.

31. Εκείνος που εξαγοράζει πράγματι την άφεση με συγχωροχάρτια είναι τόσο σπάνιος όσο εκείνος που έχει πράγματι μετανοήσει. Μάλιστα, είναι εξαιρετικά σπάνιος.

32. Όσοι πιστεύουν πως μπορούν να είναι βέβαιοι για τη σωτηρία τους επειδή αγόρασαν συγχωροχάρτια, θα είναι καταραμένοι αιώνια, μαζί με τους δασκάλους τους.

33. Οι άνθρωποι πρέπει να είναι ιδιαίτερα επιφυλακτικοί απέναντι σε όσους λένε ότι η συγχώρεση του Πάπα είναι το ανεκτίμητο δώρο του Θεού με το οποίο ο άνθρωπος συμφιλιώνεται με Εκείνον.

34. Διότι η χάρη των συγχωροχαρτιών αφορά μόνο τις ποινές της τελετουργικής ικανοποίησης που καθιέρωσε ο άνθρωπος.

35. Όσοι διδάσκουν ότι η μετάνοια δεν είναι αναγκαία εκ μέρους εκείνων που σκοπεύουν να βγάλουν ψυχές από το καθαρτήριο πληρώνοντας χρήματα ή να αγοράσουν εξομολογητικά προνόμια, διδάσκουν μη χριστιανικές διδασκαλίες.

36. Κάθε πραγματικά μετανοημένος Χριστιανός έχει δικαίωμα στην πλήρη συγχώρεση της ποινής και της ενοχής, ακόμη και χωρίς να κατέχει συγχωροχάρτι.

37. Κάθε αληθινός Χριστιανός, είτε ζωντανός είτε νεκρός, συμμετέχει σε όλες τις ευλογίες του Χριστού και της εκκλησίας, και αυτή η συμμετοχή του χορηγείται από τον Θεό, ακόμη και χωρίς να κατέχει συγχωροχάρτι.

38. Παρ' όλα αυτά, η παπική άφεση και ευλογία σε καμία περίπτωση δεν πρέπει να περιφρονείται, διότι και τα δύο αποτελούν, όπως είπα (Θέση 6), τη διακήρυξη της θείας συγχώρεσης.

39. Είναι πολύ δύσκολο, ακόμη και για τους καλύτερους θεολόγους, την ίδια στιγμή να επιδοκιμάζουν την απλοχεριά στα συγχωροχάρτια και την ανάγκη για αληθινή μετάνοια.

40. Ο Χριστιανός που μετανοεί ειλικρινά αναζητά και επιδιώκει να πληρώσει ποινές για τις αμαρτίες του. Όμως, τα απλόχερα χορηγούμενα συγχωροχάρτια μετριάζουν τις ποινές και κάνουν τους ανθρώπους να τις μισήσουν, ή τουλάχιστον τους δίνουν ευκαιρία να τις μισήσουν.

41. Τα παπικά συγχωροχάρτια πρέπει να προβάλλονται με προσοχή, μήπως και οι άνθρωποι σκεφτούν εσφαλμένα ότι τα χαρτιά αυτά πρέπει να προτιμηθούν έναντι άλλων καλών έργων αγάπης.

42. Οι Χριστιανοί πρέπει να διδαχθούν ότι σκοπός του Πάπα δεν είναι να δείξει πως η αγορά συγχωροχαρτιών πρέπει να συγκρίνεται καθ' οποιονδήποτε τρόπο με έργα ελέους.

43. Οι Χριστιανοί πρέπει να διδαχθούν ότι όποιος δίνει στους πτωχούς ή δανείζει στους έχοντες ανάγκη, κάνει καλύτερη πράξη από όποιον αγοράζει συγχωροχάρτια.

44. Επειδή η αγάπη αυξάνεται με έργα αγάπης, ο άνθρωπος γίνεται με αυτά καλύτερος. Όμως, δεν γίνεται καλύτερος με τα συγχωροχάρτια, αλλά απλώς εν μέρει απελευθερώνεται από ποινές.

45. Οι Χριστιανοί πρέπει να διδαχθούν ότι όποιος βλέπει κάποιον που έχει ανάγκη και τον προσπερνά, αλλ' ωστόσο δίνει χρήματα για την αγορά συγχωροχαρτιών, δεν εξαγοράζει την παπική άφεση αλλά την οργή του Θεού.

46. Οι Χριστιανοί πρέπει να διδαχθούν ότι, εκτός κι αν έχουν περισσότερα από όσα χρειάζονται, οφείλουν να εξοικονομούν αρκετά χρήματα για τις ανάγκες της οικογένειάς τους και σε καμία περίπτωση να μην τα σπαταλούν αγοράζοντας συγχωροχάρτια.

47. Οι Χριστιανοί πρέπει να διδαχθούν ότι η αγορά συγχωροχαρτίων είναι ζήτημα ελεύθερης επιλογής και όχι επιβολής.

48. Οι Χριστιανοί πρέπει να διδαχθούν ότι ο Πάπας, χορηγώντας συγχωροχάρτια, έχει ανάγκη και άρα επιθυμεί τις ευσεβείς προσευχές τους περισσότερο από τα χρήματά τους...

49. Οι Χριστιανοί πρέπει να διδαχθούν ότι τα παπικά συγχωροχάρτια είναι χρήσιμα μόνο αν δεν βασίζουν την πίστη τους σε αυτά, αλλά είναι πολύ επιβλαβή αν εξαιτίας τους οι Χριστιανοί χάσουν τον φόβο ενώπιον του Θεού.

50. Οι Χριστιανοί πρέπει να διδαχθούν ότι αν ο Πάπας γνώριζε την εξαναγκαστική απόσπαση χρημάτων την οποία επιβάλλουν οι ιεροκήρυκες που πωλούν τα συγχωροχάρτια, μάλλον θα προτιμούσε να καεί η Βασιλική του Αγ. Πέτρου παρά να οικοδομηθεί πάνω στο δέρμα, στη σάρκα και τα οστά του ποιμνίου του.

51. Οι Χριστιανοί πρέπει να διδαχθούν ότι ο Πάπας θα επιθυμούσε και θα έπρεπε να επιθυμεί να δώσει από τα δικά του χρήματα, ακόμα και αν έπρεπε να πωλήσει τη Βασιλική του Αγ. Πέτρου, σε πολλούς από τους οποίους κάποιοι γυρολόγοι αποσπούν χρήματα πωλώντας συγχωροχάρτια.

52. Είναι μάταιο να εμπιστεύεσαι τη σωτηρία μέσω συγχωροχαρτίων, παρ' ότι ο εκπρόσωπος του Πάπα, ή ακόμη και ο ίδιος ο Πάπας, θα πρόσφεραν την ψυχή τους ως ασφάλεια.

53. Αυτοί είναι οι εχθροί του Χριστού και του Πάπα, όσοι απαγορεύουν το κήρυγμα του Λόγου του Θεού σε ορισμένες εκκλησίες προκειμένου σε κάποιες άλλες να κηρυχθούν τα συγχωροχάρτια.

54. Ο Λόγος του Θεού πληγώνεται όταν, στο ίδιο κήρυγμα, αφιερώνεται ίσος ή περισσότερος χρόνος στα συγχωροχάρτια απ' ό,τι στον Λόγο.

55. Ασφαλώς είναι το αίσθημα του Πάπα ότι, αν τα συγχωροχάρτια, τα οποία είναι κάτι το ασήμαντο, εορτασθούν με μία κωδωνοκρουσία, μία λιτανεία, και μία ιεροτελεστία, τότε το Ευαγγέλιο, που είναι το πιο σημαντικό πράγμα, θα πρέπει να κηρυχθεί με εκατό κωδωνοκρουσίες, εκατό λιτανείες, και εκατό ιεροτελεστίες.

56. Οι αληθινοί θησαυροί της εκκλησίας, από τους οποίους ο Πάπας παίρνει και διανέμει συγχωροχάρτια, δεν έχουν συζητηθεί ούτε είναι γνωστοί επαρκώς στον λαό του Χριστού.

57. Προφανώς οι αληθινοί θησαυροί της εκκλησίας δεν είναι πρόσκαιρα αγαθά, διαφορετικά πολλοί πωλητές συγχωροχαρτίων δεν θα τα διένειμαν τόσο απλόχερα αλλά απλώς θα τα συγκέντρωναν.

58. Ούτε οι αληθινοί θησαυροί (της εκκλησίας) είναι τα ελέη του Χριστού και των αγίων, διότι αυτοί, ακόμη και χωρίς τον Πάπα, πάντα απονέμουν τη θεία χάρη στον εσωτερικό άνθρωπο, όπως παρέχουν και τον Σταυρό, τον θάνατο και την κόλαση στον εξωτερικό άνθρωπο.

59. Ο Αγ. Λαυρέντιος είπε ότι οι πτωχοί της εκκλησίας υπήρξαν οι θησαυροί της εκκλησίας, αλλά μιλούσε σύμφωνα με τη χρήση των λέξεων στην εποχή του.

60. Χωρίς έλλειψη ευαισθησίας λέμε ότι τα κλειδιά της εκκλησίας, τα οποία δόθηκαν μέσω του ελέους του Χριστού, είναι αυτός ο θησαυρός.

61. Είναι ξεκάθαρο ότι η εξουσία του Πάπα επαρκεί μόνο για την συγχώρεση ποινών και την άφεση αμαρτιών σε ιδιαίτερες περιπτώσεις, που επιφυλάσσονται για εκείνον.

62. Ο πραγματικός θησαυρός της εκκλησίας είναι το ιερότατο ευαγγέλιο της δόξας και της χάρης του Θεού.

63. Όμως ο θησαυρός αυτός είναι φυσικά εξαιρετικά επαχθής, διότι κάνει τον πρώτο έσχατο.

64. Από την άλλη, ο θησαυρός των συγχωροχαρτίων είναι φυσικά απόλυτα αποδεκτός, διότι κάνει τον έσχατο πρώτο.

65. Επομένως οι θησαυροί του ευαγγελίου είναι δίχτυα με τα οποία κάποιος στο παρελθόν ψάρευε ανθρώπους του πλούτου.

66. Οι θησαυροί των συγχωροχαρτίων είναι δίχτυα με τα οποία κάποιος σήμερα ψαρεύει τον πλούτο των ανθρώπων.

67. Τα συγχωροχάρτια, τα οποία οι δημαγωγοί επιδοκιμάζουν ως τις μεγαλύτερες χάρες είναι στην πραγματικότητα τέτοιες μόνο εφόσον αυξάνουν το κέρδος.

68. Παρ' όλα αυτά, στην πραγματικότητα είναι οι πιο ασήμαντες χάρες αν συγκριθούν με τη χάρη του Θεού και το θαυμασμό του Σταυρού.

69. Οι επίσκοποι και οι εφημέριοι είναι υποχρεωμένοι να υποδεχτούν τους απεσταλμένους με τα παπικά συγχωροχάρτια με κάθε σεβασμό.

70. Όμως ακόμη πιο υποχρεωμένοι είναι να ανοίξουν τα μάτια και τα αυτιά τους μήπως και οι άνθρωποι αυτοί κηρύσσουν τα δικά τους όνειρα αντί εκείνων που τους ανέθεσε ο Πάπας.

71. Αναθεματισμένος και καταραμένος ας είναι όποιος μιλήσει κατά της αλήθειας αναφορικά με τα παπικά συγχωροχάρτια.

72. Όμως, ευλογημένος ας είναι όποιος είναι φύλακας κατά της λαγνείας και της ακολασίας των παπικών απεσταλμένων που πωλούν συγχωροχάρτια.

73. Όπως ακριβώς και ο Πάπας δικαίως κατακεραυνώνει όσους με οποιονδήποτε τρόπο αποπειρώνται να βλάψουν τον κόσμο με αφορμή την πώληση των συγχωροχαρτίων,

74. έτσι, ακόμη περισσότερο προτίθεται να κατακεραυνώσει όσους χρησιμοποιούν τα συγχωροχάρτια ως πρόφαση για να βλάψουν την ιερά αγάπη και αλήθεια.

75. Το να θεωρεί κάποιος τα παπικά συγχωροχάρτια τόσο σπουδαία ώστε να δίνουν άφεση αμαρτιών σε κάποιον ακόμη κι αν αυτός έχει διαπράξει το αδύνατον και έχει ασκήσει βία στη μητέρα του Θεού είναι παραφροσύνη.

76. Αντιθέτως, λέμε ότι τα παπικά συγχωροχάρτια δεν μπορούν να αναιρέσουν ούτε την ελάχιστη από τις θανάσιμες αμαρτίες στο βαθμό που αφορά την ενοχή.

77. Το να λέει κάποιος ότι ακόμη και ο Αγ. Πέτρος, αν ήταν σήμερα πάπας, δεν θα μπορούσε να χορηγήσει μεγαλύτερες χάρες, αποτελεί βλασφημία κατά του Αγ. Πέτρου και του Πάπα.

78. Αντιθέτως, λέμε ότι ακόμα και ο σημερινός Πάπας, ή οποιοσδήποτε πάπας, διαθέτει μεγαλύτερες χάρες, δηλαδή το ευαγγέλιο, πνευματικές δυνάμεις, δώρα θεραπείας, κλπ. όπως είναι γραμμένο (Α' Κορ. ιβ' 12).

79. Το να λέει κάποιος ότι ο σταυρός διακοσμημένος με τον παπικό θυρεό και στημένος από τους πωλητές των συγχωροχαρτίων είναι ίσης αξίας με τον Σταυρό του Χριστού αποτελεί βλασφημία.

80. Οι επίσκοποι, οι εφημέριοι, και οι θεολόγοι που επιτρέπουν τη διάδοση τέτοιων πραγμάτων στον λαό θα πρέπει να λογοδοτήσουν γι' αυτό.

81. Αυτό το αχαλίνωτο κήρυγμα υπέρ των συγχωροχαρτίων καθιστά δύσκολο ακόμη και για τους μορφωμένους να διασώσουν τον Πάπα από τον διασυρμό ή τις δαιμόνιες ερωτήσεις των απλών ανθρώπων.

82. Όπως είναι η εξής: «Γιατί ο Πάπας δεν αδειάζει το καθαρτήριο χάριν της ιεράς αγάπης και της τρομερής κατάστασης των εκεί ευρισκόμενων ψυχών, αφού απελευθερώνει άπειρο αριθμό από ψυχές χάριν των άθλιων χρημάτων με τα οποία θέλει να φτιάξει μια εκκλησία;» Ο πρώτος λόγος θα ήταν πολύ δίκαιος, ενώ ο δεύτερος είναι πολύ ασήμαντος.

83. Επίσης, «Γιατί οι νεκρώσιμες λειτουργίες και τα ετήσια μνημόσυνα συνεχίζουν και γιατί δεν επιστρέφει ή δεν επιτρέπει την απόσυρση των δωρεών που δόθηκαν γι'αυτές, αφού είναι λάθος να προσεύχεται κανείς για τους λυτρωμένους;»

84. Επίσης, «Τι είδους ευσέβεια είναι αυτή ενώπιον του Θεού και του Πάπα ώστε με αντάλλαγμα το χρήμα να επιτρέπουν σε κάποιον ασεβή και εχθρό τους, να εξαγοράζει από το καθαρτήριο την ευσεβή ψυχή ενός φίλου του Θεού αντί, λόγω της ανάγκης αυτής της ευσεβούς και αγαπημένης ψυχής, να την απελευθερώσουν χάριν της αγνής αγάπης;»

85. Επίσης, «Γιατί οι εκκλησιαστικοί κανόνες της μετάνοιας, πολύ μετά την κατάργηση τους στην πράξη και λόγω της κατάχρησης τους, σήμερα ικανοποιούνται με τη χορήγηση συγχωροχαρτίων σαν να είναι ακόμη εν ισχύι;»

86. Επίσης, «Γιατί ο Πάπας, του οποίου ο πλούτος είναι σήμερα μεγαλύτερος από εκείνον του πλουσιότατου Κροίσσου, δεν κατασκευάζει αυτήν τη Βασιλική του Αγ. Πέτρου με δικά του χρήματα και όχι με τα χρήματα των πτωχών πιστών;»

87. Επίσης, «Τι είναι αυτό που συγχωρεί ή χορηγεί ο Πάπας σε όσους μέσω τέλειας μετάνοιας έχουν ήδη δικαίωμα σε πλήρη άφεση και ευλογία;»

88. Επίσης, «Ποια μεγαλύτερη ευλογία για την εκκλησία από εκείνη που θα προέκυπτε αν ο Πάπας απένειμε αυτές τις αφέσεις και τις ευλογίες σε κάθε πιστό εκατό φορές την ημέρα, και όχι μία όπως κάνει τώρα;»

89. «Αφού ο πάπας με τα συγχωροχάρτια επιδιώκει τη σωτηρία των ψυχών και όχι τα χρήματα, γιατί αναστέλλει τα συγχωροχάρτια και τις αφέσεις που έχουν χορηγηθεί στο παρελθόν, εφόσον έχουν ίδια αποτελεσματικότητα;»

90. Η βίαιη κατάπνιξη αυτών των πολύ καυτών ερωτήσεων του απλού λαού και όχι η απάντηση τους με λογικά επιχειρήματα εκθέτει την εκκλησία και γελοιοποιεί τον Πάπα στα μάτια των εχθρών τους και καθιστά δυστυχείς τους Χριστιανούς.

91. Εάν, επομένως, τα συγχωροχάρτια προβάλλονταν σύμφωνα με το πνεύμα και την πρόθεση του Πάπα, όλες αυτές οι αμφιβολίες θα διαλύονταν αμέσως. Μάλιστα, δεν θα υπήρχαν καν.

92. Άρα, διώξτε όλους αυτούς τους προφήτες που λένε στους ανθρώπους του Χριστού, «Ειρήνη, ειρήνη» και δεν υπάρχει ειρήνη.

93. Ευλογημένοι ας είναι όλοι εκείνοι οι προφήτες που λένε στους ανθρώπους του Χριστού, «Σταυρός, Σταυρός», και δεν υπάρχει Σταυρός.

94. Οι Χριστιανοί ας είναι επιμελείς στο να ακολουθούν τον Χριστό, την Κεφαλή τους, μέσα από ποινές, τον θάνατο και την κόλαση.

95. Κι έτσι να είναι βέβαιοι για την είσοδο τους στον παράδεισο μέσα από πολλές δοκιμασίες και όχι μέσα από την ψευδή πνευματική ασφάλεια.

* Μετάφραση: Θ. Γραμμένος,

Αστήρ της Ανατολής,

τεύχ. Οκτωβρίου 2005,

σσ. 277-280. *

[Ελληνικά/Greek, PDF)

1. Dominus et magister noster Iesus Christus dicendo `Penitentiam agite &c.' omnem vitam fidelium penitentiam esse voluit.

2. Quod verbum de penitentia sacramentali (id est confessionis et satisfactionis, que sacerdotum ministerio celebratur) non potest intelligi.

3. Non tamen solam intendit interiorem, immo interior nulla est, nisi foris operetur varias carnis mortificationes.

4. Manet itaque pena, donec manet odium sui (id est penitentia vera intus), scilicet usque ad introitum regni celorum.

5. Papa non vult nec potest ullas penas remittere preter eas, quas arbitrio vel suo vel canonum imposuit.

6. Papa non potest remittere ullam culpam nisi declarando, et approbando remissam a deo Aut certe remittendo casus reservatos sibi, quibus contemptis culpa prorsus remaneret.

7. Nulli prorus remittit deus culpam, quin simul eum subiiciat humiliatum in omnibus sacerdoti suo vicario.

8. Canones penitentiales solum viventibus sunt impositi nihilque morituris secundum eosdem debet imponi.

9. Inde bene nobis facit spiritus sanctus in papa excipiendo in suis decretis semper articulum mortis et necessitatis.

10. Indocte et male faciunt sacerdotes ii, qui morituris penitentias canonicas in purgatorium reservant.

11. Zizania illa de mutanda pena Canonica in penam purgatorii videntur certe dormientibus episcopis seminata.

12. Olim pene canonice non post, sed ante absolutionem imponebantur tanquam tentamenta vere contritionis.

13. Morituri per mortem omnia solvunt et legibus canonum mortui iam sunt, habentes iure earum relaxationem.

14. Imperfecta sanitas seu charitas morituri necessario secum fert magnum timorem, tantoque maiorem, quanto minor fuerit ipsa.

15. Hic timor et horror satis est se solo (ut alia taceam) facere penam purgatorii, cum sit proximus desperationis horrori.

16. Videntur infernus, purgaturium, celum differre, sicut desperatio, prope desperatio, securitas differunt.

17. Necessarium videtur animabus in purgatorio sicut minni horrorem ita augeri charitatem.

18. Nec probatum videtur ullis aut rationibus aut scripturis, quod sint extra statum meriti seu augende charitatis.

19. Nec hoc probatum esse videtur, quod sint de sua beatitudine certe et secure, saltem omnes, licet nos certissimi simus.

20. Igitur papa per remissionem plenariam omnium penarum non simpliciter omnium intelligit, sed a seipso tantummodo impositarum.

21. Errant itaque indulgentiarum predicatores ii, qui dicunt per pape indulgentias hominem ab omni pena solvi et salvari.

22. Quin nullam remittit animabus in purgatorio, quam in hac vita debuissent secundum Canones solvere.

23. Si remissio ulla omnium omnino penarum potest alicui dari, certum est eam non nisi perfectissimis, i.e. paucissimis, dari.

24. Falli ob id necesse est maiorem partem populi per indifferentem illam et magnificam pene solute promissionem.

25. Qualem potestatem habet papa in purgatorium generaliter, talem habet quilibet Episcopus et Curatus in sua diocesi et parochia specialiter.

1. [26] Optime facit papa, quod non potestate clavis (quam nullam habet) sed per modum suffragii dat animabus remissionem.

2. [27] Hominem predicant, qui statim ut iactus nummus in cistam tinnierit evolare dicunt animam.

3. [28] Certum est, nummo in cistam tinniente augeri questum et avariciam posse: suffragium autem ecclesie est in arbitrio dei solius.

4. [29] Quis scit, si omnes anime in purgatorio velint redimi, sicut de s. Severino et Paschali factum narratur.

5. [30] Nullus securus est de veritate sue contritionis, multominus de consecutione plenarie remissionis.

6. [31] Quam rarus est vere penitens, tam rarus est vere indulgentias redimens, i. e. rarissimus.

7. [32] Damnabuntur ineternum cum suis magistris, qui per literas veniarum securos sese credunt de sua salute.

8. [33] Cavendi sunt nimis, qui dicunt venias illas Pape donum esse illud dei inestimabile, quo reconciliatur homo deo.

9. [34] Gratie enim ille veniales tantum respiciunt penas satisfactionis sacramentalis ab homine constitutas.

10. [35] Non christiana predicant, qui docent, quod redempturis animas vel confessionalia non sit necessaria contritio.

11. [36] Quilibet christianus vere compunctus habet remissionem plenariam a pena et culpa etiam sine literis veniarum sibi debitam.

12. [37] Quilibet versus christianus, sive vivus sive mortuus, habet participationem omnium bonorum Christi et Ecclesie etiam sine literis veniarum a deo sibi datam.

13. [38] Remissio tamen et participatio Pape nullo modo est contemnenda, quia (ut dixi) est declaratio remissionis divine.

14. [39] Difficillimum est etiam doctissimis Theologis simul extollere veniarum largitatem et contritionis veritatem coram populo.

15. [40] Contritionis veritas penas querit et amat, Veniarum autem largitas relaxat et odisse facit, saltem occasione.

16. [41] Caute sunt venie apostolice predicande, ne populus false intelligat eas preferri ceteris bonis operibus charitatis.

17. [42] Docendi sunt christiani, quod Pape mens non est, redemptionem veniarum ulla ex parte comparandam esse operibus misericordie.

18. [43] Docendi sunt christiani, quod dans pauperi aut mutuans egenti melius facit quam si venias redimereet.

19. [44] Quia per opus charitatis crescit charitas et fit homo melior, sed per venias non fit melior sed tantummodo a pena liberior.

20. [45] Docendi sunt christiani, quod, qui videt egenum et neglecto eo dat pro veniis, non idulgentias Pape sed indignationem dei sibi vendicat.

21. [46] Docendi sunt christiani, quod nisi superfluis abundent necessaria tenentur domui sue retinere et nequaquam propter venias effundere.

22. [47] Docendi sunt christiani, quod redemptio veniarum est libera, non precepta.

23. [48] Docendi sunt christiani, quod Papa sicut magis eget ita magis optat in veniis dandis pro se devotam orationem quam promptam pecuniam.

24. [49] Docendi sunt christiani, quod venie Pape sunt utiles, si non in cas confidant, Sed nocentissime, si timorem dei per eas amittant.

25. [50] Docendi sunt christiani, quod si Papa nosset exactiones venialium predicatorum, mallet Basilicam s. Petri in cineres ire quam edificari cute, carne et ossibus ovium suarum.

1. [51] Docendi sunt christiani, quod Papa sicut debet ita vellet, etiam vendita (si opus sit) Basilicam s. Petri, de suis pecuniis dare illis, a quorum plurimis quidam concionatores veniarum pecuniam eliciunt.

2. [52] Vana est fiducia salutis per literas veniarum, etiam si Commissarius, immo Papa ipse suam animam pro illis impigneraret.

3. [53] Hostes Christi et Pape sunt ii, qui propter venias predicandas verbum dei in aliis ecclesiis penitus silere iubent.

4. [54] Iniuria fit verbo dei, dum in eodem sermone equale vel longius tempus impenditur veniis quam illi.

5. [55] Mens Pape necessario est, quod, si venie (quod minimum est) una campana, unis pompis et ceremoniis celebrantur, Euangelium (quod maximum est) centum campanis, centum pompis, centum ceremoniis predicetur.

6. [56] Thesauri ecclesie, unde Pape dat indulgentias, neque satis nominati sunt neque cogniti apud populum Christi.

7. [57] Temporales certe non esse patet, quod non tam facile eos profundunt, sed tantummodo colligunt multi concionatorum.

8. [58] Nec sunt merita Christi et sanctorum, quia hec semper sine Papa operantur gratiam hominis interioris et crucem, mortem infernumque exterioris.

9. [59] Thesauros ecclesie s. Laurentius dixit esse pauperes ecclesie, sed locutus est usu vocabuli suo tempore.

10. [60] Sine temeritate dicimus claves ecclesie (merito Christi donatas) esse thesaurum istum.

11. [61] Clarum est enim, quod ad remissionem penarum et casuum sola sufficit potestas Pape.

12. [62] Verus thesaurus ecclesie est sacrosanctum euangelium glorie et gratie dei.

13. [63] Hic autem est merito odiosissimus, quia ex primis facit novissimos.

14. [64] Thesaurus autem indulgentiarum merito est gratissimus, quia ex novissimis facit primos.

15. [65] Igitur thesauri Euangelici rhetia sunt, quibus olim piscabantur viros divitiarum.

16. [66] Thesauri indulgentiarum rhetia sunt, quibus nunc piscantur divitias virorum.

17. [67] Indulgentie, quas concionatores vociferantur maximas gratias, intelliguntur vere tales quoad questum promovendum.

18. [68] Sunt tamen re vera minime ad gratiam dei et crucis pietatem comparate.

19. [69] Tenentur Episcopi et Curati veniarum apostolicarum Commissarios cum omni reverentia admittere.

20. [70] Sed magis tenentur omnibus oculis intendere, omnibus auribus advertere, ne pro commissione Pape sua illi somnia predicent.

21. [71] Contra veniarum apostolicarum veritatem qui loquitur, sit ille anathema et maledictus.

22. [72] Qui vero, contra libidinem ac licentiam verborum Concionatoris veniarum curam agit, sit ille benedictus.

23. [73] Sicut Papa iuste fulminat eos, qui in fraudem negocii veniarum quacunque arte machinantur,

24. [74] Multomagnis fulminare intendit eos, qui per veniarum pretextum in fraudem sancte charitatis et veritatis machinantur,

25. [75] Opinari venias papales tantas esse, ut solvere possint hominem, etiam si quis per impossibile dei genitricem violasset, Est insanire.

1. [76] Dicimus contra, quod venie papales nec minimum venialium peccatorum tollere possint quo ad culpam.

2. [77] Quod dicitur, nec si s. Petrus modo Papa esset maiores gratias donare posset, est blasphemia in sanctum Petrum et Papam.

3. [78] Dicimus contra, quod etiam iste et quilibet papa maiores habet, scilicet Euangelium, virtutes, gratias, curationum &c. ut 1. Co. XII.

4. [79] Dicere, Crucem armis papalibus insigniter erectam cruci Christi equivalere, blasphemia est.

5. [80] Rationem reddent Episcopi, Curati et Theologi, Qui tales sermones in populum licere sinunt.

6. [81] Facit hec licentiosa veniarum predicatio, ut nec reverentiam Pape facile sit etiam doctis viris redimere a calumniis aut certe argutis questionibus laicorm.

7. [82] Scilicet. Cur Papa non evacuat purgatorium propter sanctissimam charitatem et summam animarum necessitatem ut causam omnium iustissimam, Si infinitas animas redimit propter pecuniam funestissimam ad structuram Basilice ut causam levissimam?

8. [83] Item. Cur permanent exequie et anniversaria defunctorum et non reddit aut recipi permittit beneficia pro illis instituta, cum iam sit iniuria pro redemptis orare?

9. [84] Item. Que illa nova pietas Dei et Pape, quod impio et inimico propter pecuniam concedunt animam piam et amicam dei redimere, Et tamen propter necessitatem ipsius met pie et dilecte anime non redimunt eam gratuita charitate?

10. [85] Item. Cur Canones penitentiales re ipsa et non usu iam diu in semet abrogati et mortui adhuc tamen pecuniis redimuntur per concessionem indulgentiarum tanquam vivacissimi?

11. [86] Item. Cur Papa, cuius opes hodie sunt opulentissimis Crassis crassiores, non de suis pecuniis magis quam pauperum fidelium struit unam tantummodo Basilicam sancti Petri?

12. [87] Item. Quid remittit aut participat Papa iis, qui per contritionem perfectam ius habent plenarie remissionis et participationis?

13. [88] Item. Quid adderetur ecclesie boni maioris, Si Papa, sicut semel facit, ita centies in die cuilibet fidelium has remissiones et participationes tribueret?

14. [89] Ex quo Papa salutem querit animarum per venias magis quam pecunias, Cur suspendit literas et venias iam olim concessas, cum sint eque efficaces?

15. [90] Hec scrupulosissima laicorum argumenta sola potestate compescere nec reddita ratione diluere, Est ecclesiam et Papam hostibus ridendos exponere et infelices christianos facere.

16. [91] Si ergo venie secundum spiritum et mentem Pape predicarentur, facile illa omnia solverentur, immo non essent.

17. [92] Valeant itaque omnes illi prophete, qui dicunt populo Christi `Pax pax,' et non est pax.

18. [93] Bene agant omnes illi prophete, qui dicunt populo Christi `Crux crux,' et non est crux.

19. [94] Exhortandi sunt Christiani, ut caput suum Christum per penas, mortes infernosque sequi studeant,

20. [95] Ac sic magis per multas tribulationes intrare celum quam per securitatem pacis confidant.

* D. Martin Luthers Werke : kritische Gesamtausgabe 1. Band/τόμ. 1,

Weimar: Hermann Boehlau, 1883,

pp./σσ. 233-238. *

Sunday, October 14, 2012

M. Konstantinou

on the translation of the Holy Scripture

into contemporary Greek /

Ο Μ. Κωνσταντίνου

περί της μετάφρασης της Αγίας Γραφής

στα Νέα Ελληνικά

on the translation of the Holy Scripture

into contemporary Greek /

Ο Μ. Κωνσταντίνου

περί της μετάφρασης της Αγίας Γραφής

στα Νέα Ελληνικά

|

Η εικόνα που παρουσιάζεται συχνά των "επιθετικών" δυτικών ιεραποστόλων που συνωμοτούν κατά της Ορθοδοξίας χρησιμοποιώντας τη μετάφραση του Βάμβα ως Δούρειο ίππο, δεν επαρκεί για να εξηγήσει την αποτυχία καλλιέργειας της συνεργασίας μετά της Βιβλικής Εταιρίας και της Ορθόδοξης Εκκλησίας. Μια νηφάλια και προσεκτικότερη ματιά στα πράγματα θα δείξει ότι το πρόβλημα είναι πιο περίπλοκο, και η λύση του δεν βρίσκεται στο στερεότυπο "κακοί και πονηροί δυτικοί κατά καλών και αθώων ανατολικών", αλλά απαιτεί την κατανόηση του τρόπου με τον οποίο ακόμη και τα πιο φωτεινά μυαλά εκείνης της εποχής αντιλαμβάνονταν τις ιδέες της προόδου και της πνευματικής αφύπνισης.

* Miltiadis Konstantinou / Μιλτιάδης Κωνσταντίνου,

“Bible translation and national identity:

the Greek case”

[«Η μετάφραση της Αγίας Γραφής και η εθνική ταυτότητα:

η ελληνική περίπτωση»],

International journal for the Study of the Christian Church,

Vol./Τόμ. 12, Issue/Τεύχος 2, 2012

Special Issue: Questions for Orthodox Ecclesiology: Thessaloniki Papers,

p./σ. 177 [176-186]. *

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)

.jpg)